France, mid-18th century, the clock movement by François Beliard

| Estimate: | £100,000 - £150,000 |

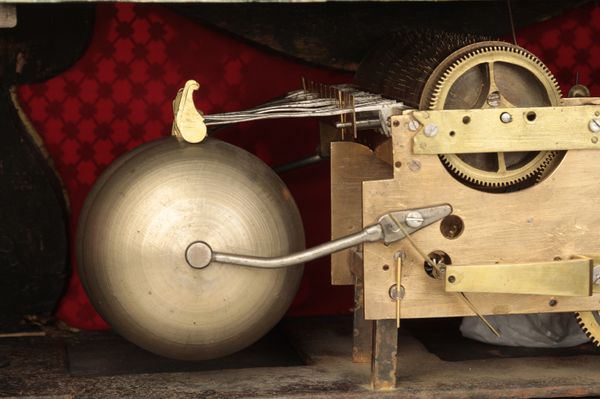

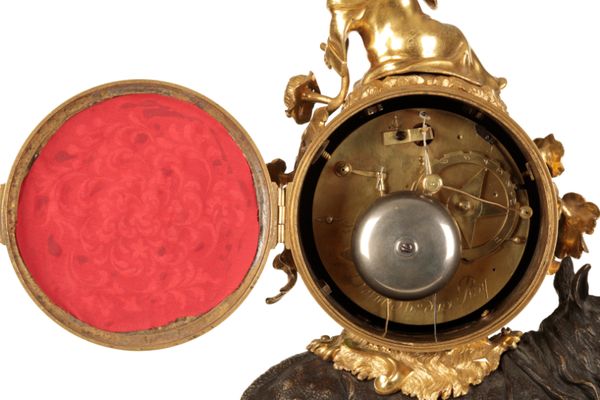

The circular white enamelled dial with Arabic and Roman chapters and pierced hands in a cylinder surmounted by an Asian figure with pig-tail holding a gourd, the twin barrel movement with silk suspension pendulum and count-wheel striking on a bell, on a bellowing rhinoceros, standing on a naturalistic rocky base with eight scrolled feet; trip lever to the plinth housing the associated musical movement in a sarcophagus-shaped box with fusee and spring pin barrel playing music on eleven bells and twelve hammers, the pierced folate trelliswork side panels lined with scarlet silk, on scrolled feet, the gilt-bronze stamped "ST GERMAIN", the dial inscribed ‘BELIARD / . H.GER * DU ROY.’, repeat signature to backplate engraved ‘Beliard hger du Roy’, with fleur-de-lys on front left side

Provenance:

Anonymous sale ('The Property of a European Noble Family'), Christie's New York, 31 October 1996, lot 417.

with Partridge Fine Arts, London, 1997 (illustrated on the cover of 'Recent Acquisitions, 1997').

The property of a Lady of Title, from 2006

This

clock was requested for loan for the exhibition Oudry's Painted Menagerie at

the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2007.

The clock depicts as its central subject, Clara the famed rhinoceros shown to fabulous acclaim for five months in Paris, from the winter of 1749 to Spring of 1750. The visit was carefully planned and the ensuing rhinomania which preceded and accompanied her visit was reflected in ladies fashions, coiffures, horse harnesses, as well as the creation of spectacular works of art.

Miss Clara

Clara was raised from birth by Jan Albert Sichterman, a Director of the Bengal region of the Dutch East India Company, and when aged about 2 years old was sold in 1740 to Douwe Mout van der Meer, a retired Dutch East India Company captain. Clara landed in Rotterdam from India in 1741. Mout van der Meer’s care of the beast across the oceans and in Europe, and meticulous planning of transportation, marketing and sale of associated commemorative wares, contributed to her achieving international celebrity status. She was the fifth rhinoceros brought to Europe from India, the previous rhinoceroses having arrived in Lisbon in 1515 (depicted in Dürer’s famous woodcut), Lisbon again in 1577 (named Abada); London in 1684 (seen by John Evelyn in October 1684 who commented on her ‘set of most dreadful teeth’); London again in 1737 and 1739. All of whom were brought to Europe for profit as touring animals.

Thanks to the Dutchman’s tireless Europe-wide tour of Clara, from 1743 until her death in 1758 and clever promotional skills, Clara came to be immortalised by numerous painters, sculptors, ceramicists and other artists. Perhaps her most important depiction was made by the French painter Jean-Baptiste Oudry, from life in 1749, when commissioned by Louis XV to include her likeness in oils in a group of paintings of animals in the menagerie at the royal palace at Versailles (although Clara was not a part of the royal menagerie). Twelve remarkable and very large paintings (the portrait of Clara measures just over 3m x 4.5m) were bought en bloc by Duke Christian Ludwig of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1750, and shown in the ducal palace in Schwerin until the 19th century when castle renovations forced the pictures into storage, where they remained, rolled up until earlier this century when they were shown in a landmark exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2007 (Oudry’s Royal Menagerie). Her visit to Paris in the winter of 1749 and Spring of 1750 was especially notable, causing the creation of spectacular works of art such as this clock, the large rhinoceros’s back especially well-suited to support the drum-shaped clock case. Clara thus directly influenced fashion: the diplomatist Baron von Grimm wrote in 1749 to the philosopher and compiler of the Encyclopédie, Denis Diderot “all Paris, so easily inebriated by small objects, is now busy with a kind of animal called rhinoceros”. There were ribbons à la rhinocéros, a satirical poem 'Le Rhinocéros'; equipage à la rhinocéros (rhinoceros carriages); even a coiffure à la rhinocéros. And the ‘rhino-manie’ spread to Florence: by 1750 Horace Mann reported to Walpole noting that Clara's visit ‘had prompted the fashion of dressing hair à la rhinocéros, which all our ladies here follow, so that the preceding mode à la comte is only for ... antiquated beauties' (though Clara never visited Florence).

Clara was transported across Europe by water where possible and where necessary in a specially designed carriage, the combined weight of which required the strength of six pairs of oxen or ten pairs of horses. She was in Holland 1741-44, visiting Brussels in 1743 and Hamburg in 1744. Thereafter and until 1758 she visited Copenhagen in the north, Naples in the south, Warsaw in the east and London in the west, where she visited on three separate occasions, and where she died in 1758. She was particularly revered in the German lands, and it seems that she was named Jungfer Clara (Miss Clara) when in Würzburg in 1748.

Clara Clocks

Of the clocks made in Paris in the years around 1750, three animal types have been identified, of which this is the second type. The rhinoceros of the first type depends on Dürer’s famous engraving of 1515 (viz. the clock with musical box sold anonymously, Sotheby’s London, 3 July 2019, lot 16 (£300,000)). The present animal is of the second type; an example (with musical box) in a public collection is in the Louvre, gift of Grog-Carven (no. OA 10540); an example with musical box sold recently, was sold anonymously at Sotheby’s Paris, 16 June 2020, lot 10 (€492,500); another of the same type, but without musical box, was sold from the Djahanguir Riahi collection, Christie’s, London, 6 December 2012, lot 18 (£181,250). The third type shows the rhinoceros’s head level with her body, mouth slightly open. An example is in the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (see T. H. Clarke, The Rhinoceros, from Dürer to Stubbs 1515-1799, London and New York, 1986, p. 132, fig. 102). The same type was depicted in the 1765 portrait of Maria-Luisa of Bourbon-Parma, by Laurent Pecheux (Galleria Palatina, Florence).

It may seem surprising that a clock depicting a rhinoceros in fashion for a short period was still en vogue by 1765, but it seems that Clara’s popularity continued long after her death in 1758. An inventory of Marie-Antoinette’s apartment at the Tuileries notes a ‘pendulum, caried by a rhinoceros posing on an ormolu gilded base…’ (E. Lery, ‘Les Pendules de Marie-Antoinette’, Revue de l’Histoire de Versailles et de Seine et Oise, 1931), and at chateau de St Cloud ‘carillon pendulum representing a rhinoceros supporting the clock and placed in a plate cabinet base (in green horn) and furnished with gilded bronze’ (Paris, Archives National, O/1/3371). The presence of a fleur-de-lys stamp on the present clock may indicate a royal ownership or inventory mark.

Jean-Joseph de St Germain (1719-1791)

Maître-fondeur in 1748, St-Germain was one of the few fondeurs to sign his name in stamped form on his work. Unlike ébénistes, who were obliged by their corporation to mark their furniture, fondeurs were not required to leave their names on their work, perhaps owing to the practical difficulty of so doing. However, St Germain (and one or two others) chose to do so, no doubt as a means of self-promotion. The stamped lettering is formed by individual letters, in order to fit into the frequently undulating surface of the gilt bronze and the confined space available. St Germain seems to have been especially associated with clocks with animal supports, especially depictions of Clara and other rhinoceroses. After he was established in the rue Saint-Nicolas a commercial prospectus noted : ‘Saint-Germain, master in chasing, modelling and founding, makes and sells all kinds of boxes and bases in tortoiseshell, gold, bronze, cabinet-fittings, fire irons, grills, chandeliers, girandoles, pendulum bases, cartel clocks of all kinds, elephant, lion, bull and other wax models, all at a fair price’. (see J.-D. Augarde, ‘Jean-Joseph de Saint-Germain (1719-1791): Bronzebearbeiten zwischen Rocaille und Klassizismus’ in H. Ottomeyer & P. Pröschel et al, Vergoldete Bronzen, Munich 1986).

The fleur-de-lys stamp is rare and is reputedly found on a pair of chenets (fire dogs) at Versailles, and on a pair of candlesticks delivered to Marie-Antoinette in 1781 for the cabinet de la Méridienne of Marie-Antoinette, perhaps the French Queen’s most perfect interior, and now in the Wallace Collection (P. Hughes, The Wallace Collection, Catalogue of Furniture, III, London, 1996, no. 243 – although no reference is made).

The shape and general design of the base or musical box, is known in other examples, including the clock in the Louvre mentioned above, OA 10540, but also as a 'stand alone' musical box: for example the Boulle marquetry and gilt-bronze-mounted musical box stamped by Antoine Foullet (1710-1775, maître in 1749) now in the Wallace Collection (F399). Jean-Joseph de St Germain was a bronzier known to have supplied mounts to Foullet. Another clock with a similar musical box, this time with a rosewood case bearing a patinated bronze sculpture of Jupiter as a bull, bearing the clock movement above which is seated Europa, in gilt bronze, bought by George Prince of Wales in 1811, and still in the Royal Collection (RCIN 30424). In the latter example, the gilt bronze is stamped by the bronzier Robert Osmond (1711-1789, maître in 1746).

François Beliard

Beliard was born into a family of clockmakers – his father was valet de chambre - horloger ordinaire du Roy, a post he achieved from 1766. He was made master in 1774 and died after 1789. He was appointed Garde en charge de sa communauté in 1771 and as a syndic in 1778. He lived in the rue de Hurepoix and was a cousin by marriage of the clockmaker Julien le Roy.

Figs:

Laurent Pecheux (1729-1821), Maria Louise of Bourbon-Parma, later Queen of Spain (detail). Florence, Galleria Palatina (c) 2022. Photo Scala, Florence - courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali e del Turismo.

H. Oster, after Beck & Schmidt, vera effigies Rhinocerotis, 1747, British Museum no. 1914,0520.687 ((c) The Trustees of the British Museum)

Rhinocerotic literature:

R. Wenley, H. Cowie, C. Avery & S. Shaw, Miss Clara and the Celebrity Beast in Art 1500-1860, London 2021, published to accompany the exhibition at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham, November 2021-February 2022.

M. Morton (ed.) Oudry’s Painted Menagerie: Portraits of Exotic Animals in Eighteenth Century Europe, Los Angeles, 2007, published to accompany the exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles May-September 2007; and at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston October 2007 – January 2008; and at the Staatliches Museum, Schwerin, April-July 2008.

T. H. Clarke, The Rhinoceros from Dürer to Stubbs 1515-1799, London & New York, 1986.

J. Durand, M. Bimbenet-Privat, F. Dassas (eds), Decorative Furnishings and Objets d’Art in the Louvre, Paris, 2014, no. 93, p. 278 (and illustrated on front cover)