when he single-handedly boarded the French “L’ Aigle”, cutlass between his teeth, on two sheets of bifold paper, the last three pages blank

Provenance: Purchased from T & W Auctions, Tunbridge Wells, November 2014. Included in several items from the papers of John Wilson Croker.

| Estimate: | £300 - £500 |

| Hammer price: | £800 |

"Jack" Spratt writes:

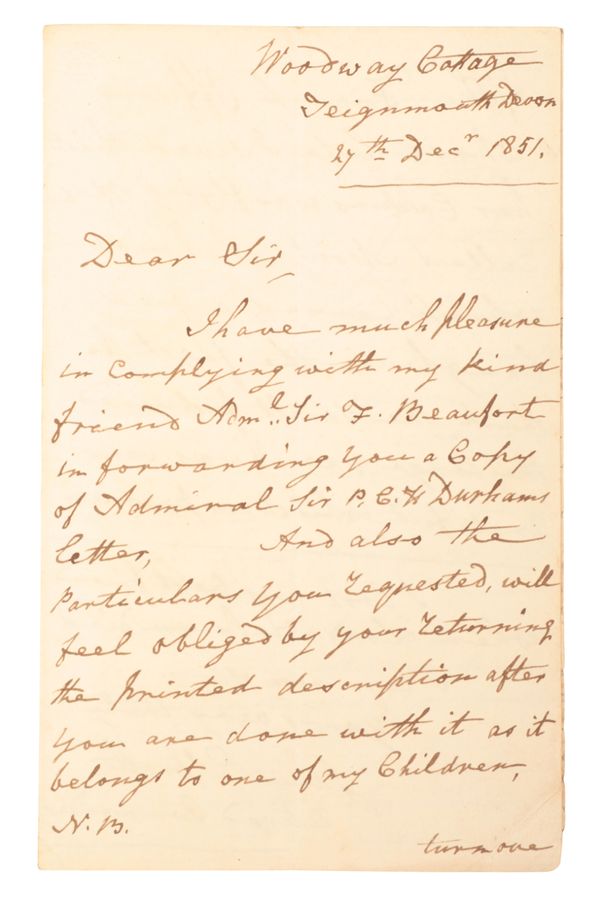

'Woodway Cottage

Teignmouth Devon

27th Dec 1851

Dear Sir,

I have much pleasure in complying with my kind friend Adml Sir F. Beaufort in forwarding you a copy of Admiral Sir P.C.H. Durham’s letter, and also the particulars you requested, will feel obliged by your returning the printed description after you are done with it, as it belongs to one of my children. NB. Turn over.

The French Officers whose life I saved whilst her colours was flying was called Mons. Salmon which caused a great laugh in the fleet to think the small fish saved the large one, & was very grateful whilst our prisoner.

I lost my best friend when Lord Nelson died.

I remain sir,

Yours very truly,

James Spratt

Retired Commander.''

The following three leaves, in Spratt's own hand, contain an account of his remarkable Trafalgar actions in the words of his Captain, Philip Durham, who witnessed the event. Durham had written a letter to Spratt thirty-three years after the battle, which Spratt has copied, as follows:

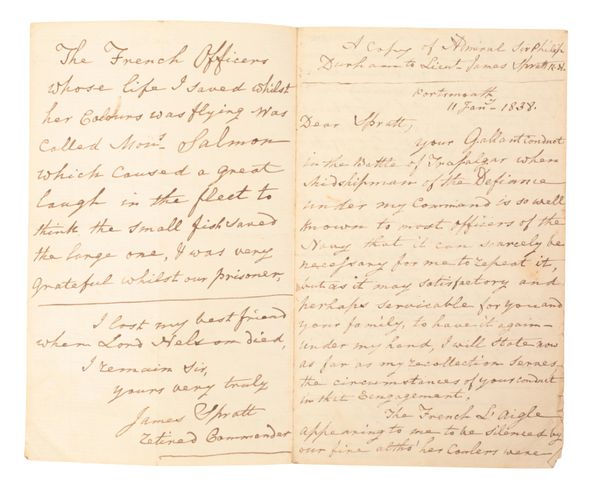

"A Copy of Admiral Sir Philip Durham to Lieut James Spratt R.N.

Portsmouth

11 Jany 1838

Dear Spratt,

Your Gallant conduct in the Battle of Trafalgar when Midshipman of the Defiance under my Command is so well known to most officers of the Navy that is can scarcely be necessary for me to repeat it, but as it may satisfactory and perhaps serviceable for you and your family, to have it again – under my hand, I will state now as far as my recollection serves, the circumstances of your conduct in that engagement.

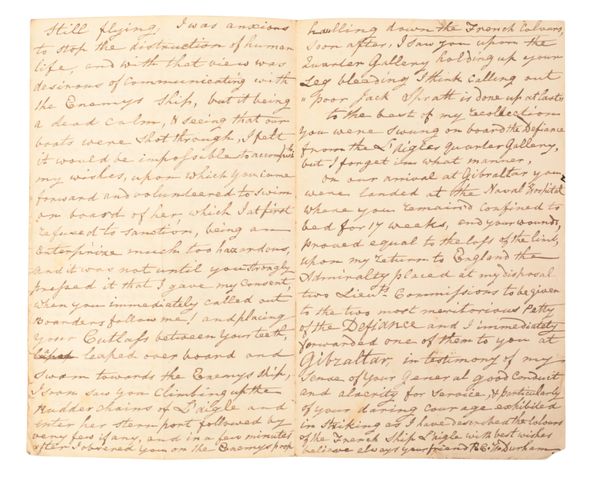

The French L’Aigle appearing to me to be silenced by our fire although her coulers (sic) were still flying, I was anxious to stop the destruction of human life, and with that view was desirous of communicating with the Enemys ship, but it being a dead calm, & seeing that our boats were shot through, I felt it would be impossible to accomplish my wishes, upon which you came forward and volunteered to swim on board of her, which I at first refused to sanction, being an enterprise much too hazardous, and it was not until you strongly pressed it that I gave my consent, when you immediately called out Boarders follow me! And placing your cutlass between your teeth leaped over board and swam towards the Enemys ship. I soon saw you climbing up the rudder chains of L’aigle and enter her stern port followed by very few if any, and in a few minutes after I observed you in the Enemys poop hauling down the French colours, soon after, I saw you upon the Quarter Gallery holding up your leg bleeding I think calling out “Poor Jack Spratt is done up at last.”

To the best of my recollection you were swung on board the Defiance from the L’Aigle Quarter Gallery, but I forget in what manner.

On our arrival at Gibraltar you were landed at the Naval Hospital where you remained confined to bed for 17 weeks, and your wounds proved equal to the loss of the limb. Upon my return to England the Admiralty placed at my disposal two Lieuts. Commissions to be given to the two most meritorious Petty of the Defiance and I immediately forwarded one of them to you at Gibraltar, in testimony of my sense of your general good conduct and alacrity for service, & particularly of your daring courage exhibited in striking as I have described the Colours of the French ship L’aigle. With best wishes, believe me always your friend

R.C.H.Durham."

Note: Dublin born James Spratt (1771-1853), on a day when there were countless acts of courage on both sides, performed arguably the most remarkable and certainly well-known single act of heroism, when he attempted to take L’aigle single-handedly, with his cutlass in his teeth and battleaxe in hand. A strong swimmer (uncommon amongst sailors of the day), he had entered the stern gunroom port of the Frenchman, and fought his way through all the decks until he reached the poop. Charged by three grenadiers with fixed bayonets, he disabled two of them and killed the third. By this time a boarding party from the Defiance had arrived, and Spratt joined in the hand-to-hand combat, when a French Grenadier tried to run him through with his bayonet. He parried the thrust, whereby the Frenchman fired his musket at Spratt’s chest. Spratt succeeded in striking the musket with his cutlass, so that the charge passed through his right leg, shattering both bones.

Taken back to the Defiance, a few days later Surgeon Mr Burnett asked for a written order to amputate Spratt’s leg, saying that the man had refused to submit to the operation, but it could not be cured. Captain Durham refused, and despite his own wounds visited Spratt to remonstrate with him, whereby Spratt held out his good leg and exclaimed “Never! If I lose my leg where shall I find a match for this?”

Spratt kept his injured leg, though he remained lame all his life. He eventually became a Commander, and was pensioned off in 1838. Despite one leg being three inches shorter than the good one, he remained a strong swimmer, and received several commendations for saving people from drowning in the sea off Teignmouth, where he retired.

References: Adkin, Mark. The Trafalgar Companion (2009)

Warwick, Peter. Voices from the Battle of Trafalgar (2005)

The whereabouts of Captain Durham’s original letter to Spratt, which “belongs to one of my children” is unknown.